© Vasco Stocker Vilhena

Juan Araujo | Robert Barry | Tomory Dodge | Jack Goldstein | Vera Lutter | Julião Sarmento | Rirkrit Tiravanija | João Pedro Vale + Nuno Alexandre Ferreira | Yonamine | Lawrence Weiner | Fischli and Weiss

Places

A few decades ago, people still went “for a little outing” to the airport to watch the planes. In those days, the airport could still be regarded as a site, a destination — something one might reasonably call a place. In its traditional sense, a place is tied to the anchoring and delineation of identity, territory, and a group’s rootedness. The most obvious examples are the age-old notions of “land” or “home”.

“‘Non-place’ would thus be a place that is not relational, not identitary, and not historical. It materialises in motorways, airports, and large retail complexes.”(1) Today, an airport merely provides, with varying degrees of discomfort, a passage towards what we imagine to be an actual destination. No matter how large, no matter how overcrowded, the airport remains empty, a nothingness.

Peter Fischli and David Weiss’s Airport (Frankfurt – Condor), made between 1998 and 2000, is a Cibachrome print on Syntac and forms part of the series 800 Views of Airports, in which the duo document images of seemingly anonymous airports, between departures and arrivals, during their travels across the world.

Using the camera obscura and the silver-gelatine enlargement process on paper, Vera Lutter leads us this time into the interior of the hangar — Frankfurt Airport XV: Hangar 5: May 7–15 (2001). This diptych is part of a photographic project begun in 1997 on the themes of travel, transport, and expeditions.

Destinations

Between places and non-places, there are paths. We speak of expectations, aims, horizons, destinations: the tricks and traps of thought.

“Now One Sees It”, “Now One Don’t”, “Here Is It”, “Here Is It Not.”

Lawrence Weiner said that his works were “sculptures”, and that reading these phrases should prompt a form of attention and reflection that leads to questions such as “what is this place I’m in?”, “what am I doing here?”, “where do I go from here?” The artist offers no answers. Each person must follow their own route.

Two characters cross paths in the desert and sketch a fragile dialogue:

“Where you going?”

“I don’t know! You wanna help?”(2)

In Fin de Siécle (2024), João Pedro Vale and Nuno Alexandre Ferreira dress up as Superman and set off towards a giant iceberg. It evokes, on one hand, the wreckage in Caspar David Friedrich’s painting The Sea of Ice (1823) and, on the other, General Idea’s 1990 installation of the same title. Or perhaps they advance towards a formation of kryptonite — a crystal known for weakening the superhero — anticipating a moment of sacrifice or self-destruction.

Things

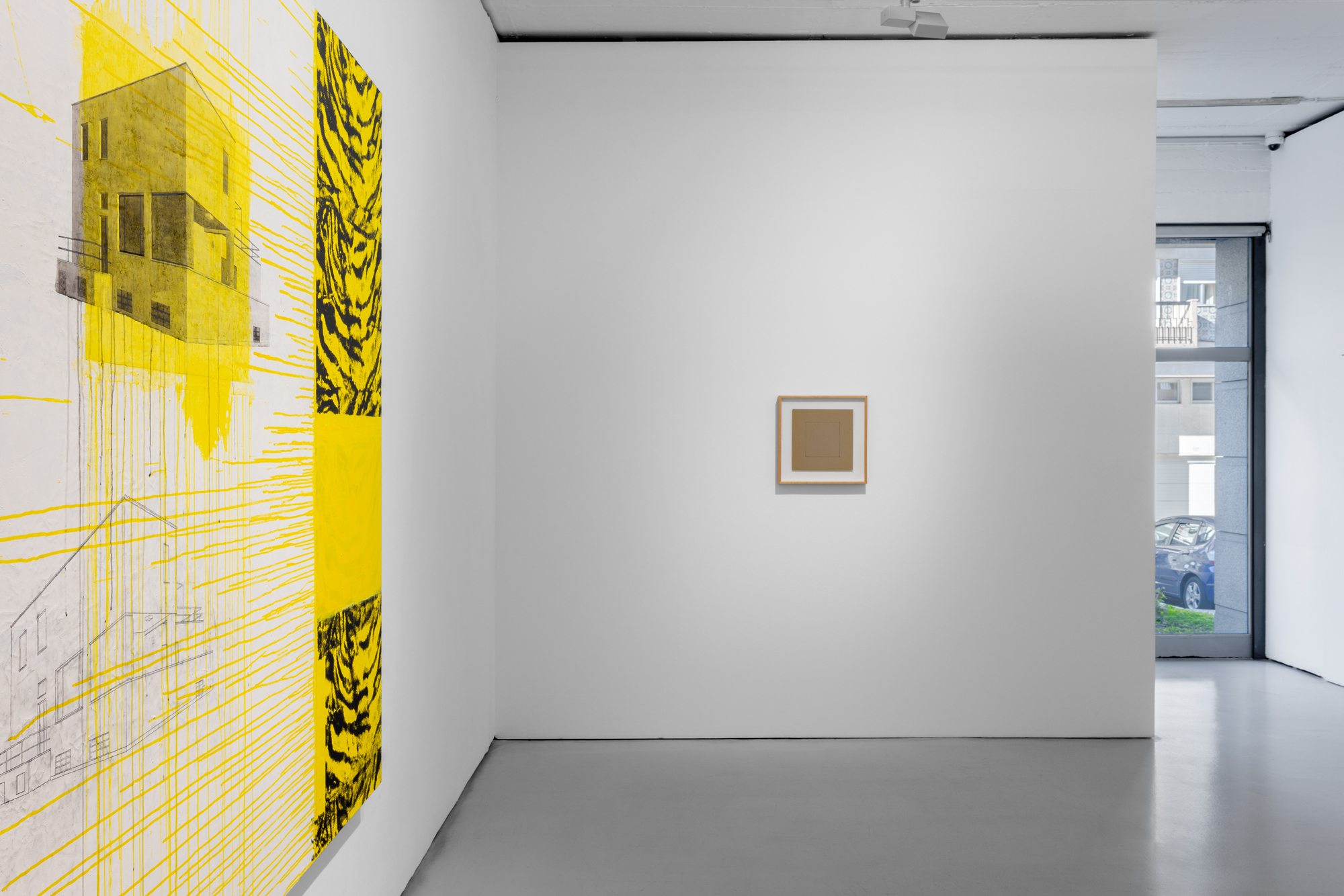

One might say that, in places or non-places, things persist. Walter Gropius’s architectural design for the Bauhaus Masters’ House in Dessau — destroyed during the Second World War — survives as an idea. In Gropius Yellow Tiger (2011–2018), Julião Sarmento evokes a thing, but this is the beginning of a conversation, not a conclusion nor a finished place. Lines, patches, pelts, and colours must all be assembled. After all, it is not a house: it is a painting.

The works of Tomory Dodge seem to explore a kind of glitch — a failure, collapse, or interference — in which the image operates at a threshold between representation and abstraction. In Salton Sargasso (2005), Dodge did not paint a parallelepiped resembling a building, a mailbox, or a bus. He painted a painting.

Where there is an idea, there is a story: products of imagination, the capacity to produce images.

Let us consider the fable told by Yonamine:

A bee asked a healer for help to save her sick child. He replied that he would need a cuckoo’s feather. The cuckoo, in solidarity, gave one of his feathers. Later, the cuckoo’s own child fell ill, and the healer explained that only a bee’s wing could cure him. The bee refused, claiming she had only two wings. Hurt, the cuckoo vowed to reveal to humans where bees hide their honey. Cuco e Abelha (2025) is a story, a breath, a reaction, anything that has a spark. Using a highly flammable material used in the production of matches, Yonamine captures the tension and implicit balance between gesture and flame.

All of it invented, imagined, turned into image.

Juan Araujo’s Novus Orbis (2019–2020) recounts a story imagined by the first Spaniards to reach South America. The work revisits the episode behind the naming of a country — Venezuela. During an expedition at the end of the fifteenth century, explorers encountered stilt houses used by coastal Indigenous communities. The sight of these dwellings rising over the water reminded them of Venetian architecture, leading them to name the territory Venezuela — “Little Venice” of Spain.

Araujo’s painted images are so perfect that they appear to depict reality itself. Yet what grants them their ideal sense of the real is precisely that they are pictorial reproductions of pre-existing images, in this case drawn from the internet, tied to how someone once imagined and mapped a place.

In the end, space does not quite exist — only two-dimensional images, as if on screens. We do not enter or walk through spaces; we make camera movements with the eye and perform more or less sophisticated image editing. Everything is an image-making process. To imagine non-existent three-dimensional things, Robert Barry’s lines will suffice.

Disappearing

Where is Jack Goldstein? (2002), oil on canvas by Rirkrit Tiravanija.

At the 1972 CalArts graduation exhibition, a faint blinking red light went almost unnoticed. The light was connected to Jack Goldstein’s heartbeat; the artist himself had vanished beneath the floor, breathing through a plastic tube.(3) From the early 1990s onwards, Goldstein’s whereabouts were unknown. It was eventually discovered that he was living in a trailer with no water or electricity, absorbed in substances producing peculiar effects.

Between these two disappearances, he painted several hundred of the most remarkable and unclassifiable works of the period. He took his own life in 2003.

“Dazzling light occupies the centre of every painting, and Goldstein himself said that light illuminates the darkness of images such that ‘there are no longer any dark secrets’ […] Light is displayed as sheer effect to its fullest capacity, in all its variations. It is displayed in its absolute depletion, its immaterial nothingness.”(4)

If all goes well, that is where we shall be heading. To Heaven.

Alexandre Melo

(1) Filomena Silvano, Antropologia do Espaço, 2017, p.100.

(2) Gerry, directed by Gus Van Sant, 2002, minute 57.

(3) Jack Goldstein and the CalArts Mafia, Richard Hertz, 2003.

(4) Philipp Kaiser in Jack Goldstein x 10000, 2012, p.133.